Posted: 4/4/2019 | April 4th, 2019

A few years ago, I read the book The Year of Living Danishly by Helen Russell. I think it originally came up as a suggested book on Amazon. I can’t fully remember. But, I stuck it in my queue, ordered it, and it sat on my bookshelf until it was time to read it. I couldn’t put it down. It was funny, well written, interesting, and an insightful look into Danish culture. It was one of my favorite books I read that year.

Last year, I somehow convinced Helen to speak at TravelCon and got to meet her in person. Now, she has a new book out called The Atlas of Happiness. It’s about why people in certain places are happier than others. It’s a phenomenal book (you should get it). Today, Helen shares some of what she learned in researching that book!

Here’s a funny thing: if you’ve been online today for more than a fraction of a second, you may have started to get the sense that the world is A Terrible Place. Even the committed traveler with an open mind could be forgiven for thinking that the outlook is pretty bleak.

And if you’ve seen the headlines today or been on social media and you’re feeling low as a result, you’re not alone.

It’s easy to get the idea that the world is becoming more miserable by the minute and that happiness is a luxury in these troubled times.

But over the past six years, I’ve learned that there are people all around the world finding ways to stay happy, every day. And that happiness is something we’re hardwired to seek out – wherever we are.

I started researching happiness in 2013 when I relocated from the UK to Denmark. I’d spent 12 years living and working in London as a journalist, and I had no intention of leaving, until out of the blue one wet Wednesday, my husband came home and told me he’d been offered his dream job…working for Lego in rural Jutland. I was skeptical to start with — I had a good career, a nice flat, great friends, close family — I had a life.

Okay, so my husband and I both worked long hours, we were tired all the time, and never seemed to be able to see each other very much. We regularly had to bribe ourselves to get through the day and we’d both been ill on and off for the past six months.

But that was normal, right?

We thought we were ‘living the dream.’ I was 33 years old and we’d also been trying for a baby for as long as either of us could remember, enduring years of fertility treatment, but we were always so stressed that it never quite happened.

So when my husband was offered a job in Denmark, this ‘other life’ possibility was dangled in front of us — the chance to swap everything we knew for the unknown. Denmark had just been voted the world’s happiest country in the UN’s annual report and I became fascinated by this. How had a tiny country of just 5.5m people managed to pull off the happiest nation on earth title? Was there something in the water? And if we couldn’t get happier in Denmark, where could we get happier?

During our first visit, we noticed that there was something a bit different about the Danes we met. They didn’t look like us, for starters — quite apart from the fact that they were all strapping Vikings towering over my 5’3” frame — they looked more relaxed and healthier. They walked more slowly. They took their time to stop and eat together, or talk, or just…breathe.

And we were impressed.

My Lego Man husband was sold on the idea and begged me to move, promising we’d relocate for my career next time. And I was so worn out by my hectic London life that I found myself agreeing. I quit my job to go freelance and decided I would give it a year, investigating the Danish happiness phenomenon first hand — looking at a different area of living each month to find out what Danes did differently.

From food to family life; work culture to working out; and design to the Danish welfare state — each month I would throw myself into living ‘Danishly’ to see if it made me any happier and if I could change the way I lived as a result. I decided I would interview as many Danes, expats, psychologists, scientists, economists, historians, sociologists, politicians, everyone, in fact, to try to uncover the secrets to living Danishly.

I documented my experiences for two UK newspapers before being asked to write a book: The Year of Living Danishly, Uncovering the Secrets of the World’s Happiest Country.

Since then, I’ve been humbled and moved to hear from readers from across the globe with wide-ranging life perspectives, but the one constant was a need to share the happiness secrets of their own cultures. Some of the themes that sprung out were universal — such as social interactions, exercising out of doors and finding a balance in life — while others were intriguingly unique.

So I set out to research into unique happiness concepts from around the world, interviewing people internationally until The Atlas of Happiness — my new book-baby — was born. It isn’t a compendium of the happiest countries; instead, it’s a look at what’s making people happier in different places. Because if we only look at the countries already coming top of the happiness polls, we miss out on ideas and knowledge from cultures we’re less familiar with.

So I set out to research into unique happiness concepts from around the world, interviewing people internationally until The Atlas of Happiness — my new book-baby — was born. It isn’t a compendium of the happiest countries; instead, it’s a look at what’s making people happier in different places. Because if we only look at the countries already coming top of the happiness polls, we miss out on ideas and knowledge from cultures we’re less familiar with.

Nowhere is perfect. Every country has faults. But I wanted to celebrate the best parts of a country’s culture as well as national characteristics at their finest – because that’s what we should all be aiming for.

Here are a few of my favorites:

Did you know, for example, that in Portuguese there’s something called saudade — a feeling of longing, melancholy, and nostalgia for a happiness that once was — or even a happiness you merely hoped for?

And while Brazil may be famous for its carnival spirit, the flipside of this, saudade, is so central to the Brazilian psyche that it’s even been given its own official ‘day’ on the 30th of January every year.

Most of us will have experienced a bittersweet pleasure in moments of melancholy — flicking through old photos, or caring about anyone enough to miss them when they’re gone.

And scientists have found that this temporary sadness — counter-intuitively — makes us happier: providing catharsis; improving our attention to detail; increasing perseverance and promoting generosity. So we should all spend time remembering those we’ve loved and lost — then practice being a little more grateful for the ones still around.

Finland ranked number one in this year’s UN World Happiness report thanks to a great quality of life, free healthcare, and education funded by high taxes.

But there’s also something else the Finns enjoy that’s infinitely more exportable: kalsarikännit — defined as ‘drinking at home in your underwear with no intention of going out’ — a pursuit so popular it even has its own emoji, commissioned by The Finnish Foreign Ministry.

In common with most Scandinavians, Finns aren’t shy about disrobing, and they all have such enviably well-insulated houses that stripping down to their pants is apparently completely okay even when it’s minus 35 degrees outside. What you drink and crucially how much of it you knock back is down to the individual, but it’s a uniquely Finnish form of happiness and mode of relaxation that we can all give a go.

In Greece, they have a concept called meraki that refers to an introspective, precise expression of care, usually applied to a cherished pastime — and it’s keeping Greeks happy despite turbulent times. This is because having a hobby improves our quality of life according to scientists, and challenging ourselves to do something different also creates new neural pathways in our brain. Having a passion that you take pride can be of extra benefit to those who can’t say the same for their primary occupation.

Because meraki can make life worthwhile if your 9-5 is more of a daily grind. Many tasks that need to be taken care of on a day-to-day basis aren’t particularly challenging or inspiring – from filing, to raising purchase orders or even — dare I say it — some of the more gruelling aspects of parenting.

But we can break up the never-ending cycle of mundane work with our own personal challenges — things that we’re passionate about that we can genuinely look forward to doing. Our meraki.

Dolce far niente — or the sweetness of doing nothing — is a much-treasured concept in Italy — often hashtagged on Instagram accompanying pictures of Italians in hammocks. Okay, so Italy hasn’t exactly topped any happiness rankings in recent years, but the cliché of the carefree Italian still exists – and with good reason.

Italians do ‘nothing’ like no other nation and perfecting the art takes style and skill – because there’s more to it than meets the eye. It’s watching the world go by over coffee and a cornetto. It’s laughing at tourists. Or politicians. And crucially it’s about savoring the moment and really enjoying the present. Many of us search for relaxation by traveling to exotic locations, drinking to oblivion, or trying to blot out the noise of modern life.

But Italians let the chaos wash over them. Instead of saving up our ‘fun quota’ for an annual escape, they spread it over the minutes, hours and days throughout the year and ‘enjoy life’ in all its messy reality.

One of the happiest countries in the world, the Norwegians must be doing something right. And quite aside from their enviable Scandi-lifestyles and the safety net of all that oil, Norwegians have a secret ace card up their sleeves: a concept called friluftsliv. This roughly translates as ‘free air life’ and it’s a code of conduct as well as a life goal for most Norwegians – who like to spend time outdoors and get high, as often as possible.

Anyone who’s ever visited the country will know that if you meet a Norwegian out in nature, their objective tends to be the highest mountain nearby – and there’s a saying in Norway that “You must make an effort before you can have pleasure’.

Most Norwegians believe you have to work for things, to earn them with physical endeavors, battling the elements. Only once you’ve climbed a mountain in the rain and cold, can you truly enjoy your dinner. It’s an old fashioned approach to the good life but numerous studies show that using our bodies and getting out into nature as often as possible boosts mental and physical wellbeing.

Which is all very well, on paper. But how to apply these principles and all the things I’d learned in real life? Well, I took it slowly — dolce far niente style. I had to learn not to be the archetypal Londoner, working all hours. Instead, I had to try relaxing once in a while.

Radical, I know.

Next, I got on the hobby train. I found my meraki in pottery, in cooking and trying out new recipes, often inspired by the countries I was researching. Some weeks, we ate well. Others, not so much (my husband still hasn’t forgiven me for ‘Russian month’). I’m not ashamed to say that I’ve done a fair amount of underwear-drinking, too.

The Finnish concept of kalsarikännit and I are now firm friends. And because I was working less and being more mindful of living well and looking after myself, it was relatively easy to adopt the Norwegian ethos of friluftsliv.

So now I try to ask myself: what did I do today? What did I climb? Where did I go? But the biggest mind shift was the realization that to be happy, we have to be comfortable being sad sometimes, too. That we’re at our healthiest and happiest when we can reconcile ourselves to all our emotions, good and bad.

The Portuguese saudade was a game changer for me — helping me to come to terms with the life I thought I’d have and find a way to move on, without resentment or bitterness. Because when you let go of these things, something pretty amazing can happen.

By learning from other cultures about happiness, wellbeing and how to stay healthy (and sane), I found a way to be less stressed than I was in my old life. I developed a better understanding of the challenges and subtleties of coming from another culture. My empathy levels went up. I learned to care, more.

Optimism isn’t frivolous: it’s necessary. You’re travelers. You get this. But we need to spread the word, now, more than ever. Because we only have one world, so it would be really great if we didn’t mess it up.

Hellen Russell is a British journalist, speaker, and the author of the international bestseller The Year of Living Danishly. Her most recent book, The Atlas of Happiness, examines the cultural habits and traditions of happiness around the globe. Formerly the editor of marieclaire.co.uk, she now writes for magazines and newspapers around the world, including Stylist, The Times, Grazia, Metro, and The i Newspaper.

Book Your Trip: Logistical Tips and Tricks

Book Your Flight

Find a cheap flight by using Skyscanner or Momondo. They are my two favorite search engines because they search websites and airlines around the globe so you always know no stone is left unturned.

Book Your Accommodation

You can book your hostel with Hostelworld as they have the largest inventory. If you want to stay somewhere other than a hostel, use Booking.com as they consistently return the cheapest rates for guesthouses and cheap hotels. I use them all the time.

Don’t Forget Travel Insurance

Travel insurance will protect you against illness, injury, theft, and cancellations. It’s comprehensive protection in case anything goes wrong. I never go on a trip without it as I’ve had to use it many times in the past. I’ve been using World Nomads for ten years. My favorite companies that offer the best service and value are:

Looking for the best companies to save money with?

Check out my resource page for the best companies to use when you travel! I list all the ones I use to save money when I travel – and that will save you time and money too!

The post The Atlas of Happiness: Discovering the World’s Secret to Happiness with Helen Russell appeared first on Nomadic Matt's Travel Site.

Posted: 01/27/2020 | January 27th, 2020

In 2010, I decided to spend the summer in NYC. I was two years into blogging and was making enough where I could afford a few months here. Still new to the industry, NYC was where all the legends of writing lived and I wanted to start making connections with my peers.

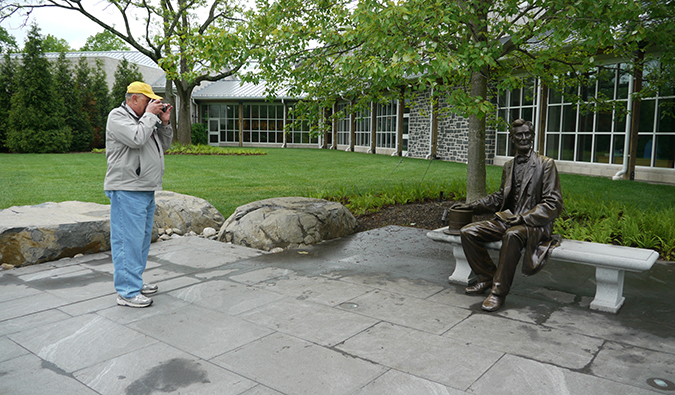

It was that summer I met Jason Cochran, a guidebook writer from Frommers, editor, and the man I would consider my mentor.

Though we never had any formal mentor/mentee relationship, Jason’s writing philosophy, advice, and feedback, especially on my first book, How to Travel the World on $50 a Day, has been instrumental in shaping me as a writer. Much of his philosophy has become mine and I don’t think I would have grown to where I am without him.

Last year, he finally published the book he’d been working on about tourism in America, called Here Lies America. (We featured it on our best books of 2019 list).

Today, we’re going to go behind the scenes of the book and talk to Jason on what does lie in America!

Nomadic Matt: Tell everyone about yourself.

Jason Cochran: I’ve been a travel writer for longer than I’ve felt like an adult. In the mid-‘90s, I kept a very early form of a travel blog on a two-year backpacking trip around the world. That blog became a career. I’ve written for more publications than I can count, including for a prime-time game show.

These days I’m the Editor-in-Chief of Frommers.com, where I also write two of its annual guidebooks, and I co-host a weekly radio show with Pauline Frommer on WABC. For me, history is always my way into a new place. In many ways, time is a form of travel, and understanding the past flexes a lot of the same intellectual muscles as understanding cultural differences.

So I have come to call myself a travel writer and a pop historian. That last term is something I just made up. Dan Rather made fun of me once for it. “Whatever that is,” he said. But it seems to fit. I like uncovering everyday history in ways that are funny, revealing, and casual, the way Bill Bryson and Sarah Vowell do.

What made you want to write this book?

Before I began researching, I just thought it would be funny. You know, sarcastic and ironic, about Americans going to graveyards and places of suffering just to buy lots of tacky souvenirs, eat ice cream, and wear dumb t-shirts. And, that’s still in there, for sure. We’re Americans and we like those things. Key chains will happen.

But that changed fast. For one, that would have become a very tired joke. It wouldn’t carry for three hundred pages. Things clicked for me early on, on the first of several cross-country research drives I took. I went to a place that I wasn’t taught about at school, and it clicked. I was at Andersonville in rural Georgia, where 13,000 out of 45,000 Civil War prisoners died in just 14 months. It was flat-out a concentration camp.

Yes, it turns out that concentration camps are as American as apple pie. The man who ran it was the only Confederate officer who was executed after the war. Southerners feared the victors would hang their leaders by the dozen, but that vengeance never materialized. Not for Jefferson Davis, not for Robert E. Lee—the guy who ran this camp poorly got the only public hanging. And he wasn’t even a born American. He was Swiss!

But that’s how important this place was at the time. Yet most of us have never even heard of it, except for a really bad low-budget movie on TNT in the ‘90s in which all the characters bellowed inspirational monologues as if they thought they were remaking Hoosiers.

So just getting my head around the full insanity of Andersonville’s existence was a big light bulb—our history is constantly undergoing whitewashing. Americans are always willfully trying to forget how violent and awful we can be to each other.

And Andersonville wasn’t even the only concentration camp in that war. There were a bunch in both the North and the South, and most of them had survival rates that were just as dismal. So that was another light bulb: There’s a story in why our society decided to preserve Andersonville but forget about a place like Chicago’s Camp Douglas, which was really just as nasty, except now it’s a high-rise housing project and there’s a Taco Bell and a frozen custard place where its gate once stood.

And did you know that the remains of 12,000 people from another Revolutionary War concentration camp are in a forgotten grave smack in the middle of Brooklyn? We think our major historic sites are sacred and that they are the pillars of our proud American story, but actually, how accurate can our sites be if they’re not even fairly chosen?

Posted: 01/27/2020 | January 27th, 2020

In 2010, I decided to spend the summer in NYC. I was two years into blogging and was making enough where I could afford a few months here. Still new to the industry, NYC was where all the legends of writing lived and I wanted to start making connections with my peers.

It was that summer I met Jason Cochran, a guidebook writer from Frommers, editor, and the man I would consider my mentor.

Though we never had any formal mentor/mentee relationship, Jason’s writing philosophy, advice, and feedback, especially on my first book, How to Travel the World on $50 a Day, has been instrumental in shaping me as a writer. Much of his philosophy has become mine and I don’t think I would have grown to where I am without him.

Last year, he finally published the book he’d been working on about tourism in America, called Here Lies America. (We featured it on our best books of 2019 list).

Today, we’re going to go behind the scenes of the book and talk to Jason on what does lie in America!

Nomadic Matt: Tell everyone about yourself.

Jason Cochran: I’ve been a travel writer for longer than I’ve felt like an adult. In the mid-‘90s, I kept a very early form of a travel blog on a two-year backpacking trip around the world. That blog became a career. I’ve written for more publications than I can count, including for a prime-time game show.

These days I’m the Editor-in-Chief of Frommers.com, where I also write two of its annual guidebooks, and I co-host a weekly radio show with Pauline Frommer on WABC. For me, history is always my way into a new place. In many ways, time is a form of travel, and understanding the past flexes a lot of the same intellectual muscles as understanding cultural differences.

So I have come to call myself a travel writer and a pop historian. That last term is something I just made up. Dan Rather made fun of me once for it. “Whatever that is,” he said. But it seems to fit. I like uncovering everyday history in ways that are funny, revealing, and casual, the way Bill Bryson and Sarah Vowell do.

What made you want to write this book?

Before I began researching, I just thought it would be funny. You know, sarcastic and ironic, about Americans going to graveyards and places of suffering just to buy lots of tacky souvenirs, eat ice cream, and wear dumb t-shirts. And, that’s still in there, for sure. We’re Americans and we like those things. Key chains will happen.

But that changed fast. For one, that would have become a very tired joke. It wouldn’t carry for three hundred pages. Things clicked for me early on, on the first of several cross-country research drives I took. I went to a place that I wasn’t taught about at school, and it clicked. I was at Andersonville in rural Georgia, where 13,000 out of 45,000 Civil War prisoners died in just 14 months. It was flat-out a concentration camp.

Yes, it turns out that concentration camps are as American as apple pie. The man who ran it was the only Confederate officer who was executed after the war. Southerners feared the victors would hang their leaders by the dozen, but that vengeance never materialized. Not for Jefferson Davis, not for Robert E. Lee—the guy who ran this camp poorly got the only public hanging. And he wasn’t even a born American. He was Swiss!

But that’s how important this place was at the time. Yet most of us have never even heard of it, except for a really bad low-budget movie on TNT in the ‘90s in which all the characters bellowed inspirational monologues as if they thought they were remaking Hoosiers.

So just getting my head around the full insanity of Andersonville’s existence was a big light bulb—our history is constantly undergoing whitewashing. Americans are always willfully trying to forget how violent and awful we can be to each other.

And Andersonville wasn’t even the only concentration camp in that war. There were a bunch in both the North and the South, and most of them had survival rates that were just as dismal. So that was another light bulb: There’s a story in why our society decided to preserve Andersonville but forget about a place like Chicago’s Camp Douglas, which was really just as nasty, except now it’s a high-rise housing project and there’s a Taco Bell and a frozen custard place where its gate once stood.

And did you know that the remains of 12,000 people from another Revolutionary War concentration camp are in a forgotten grave smack in the middle of Brooklyn? We think our major historic sites are sacred and that they are the pillars of our proud American story, but actually, how accurate can our sites be if they’re not even fairly chosen?

What was one of the most surprising things you learned from your research?

In almost no instance was a plaque, statue, or sign placed right after the historic event in question. Most of the monuments were actually installed many decades after the event. In the case of the Civil War, most of the memorials were erected in a boom that came a half-century after the last bullet was fired.

If you really get close to the plaques and read past the poetic inscriptions, it quickly becomes clear that our most beloved historic sites aren’t sanctified with artifacts but with propaganda placed there by people who weren’t even witnesses to the event. There was a vast network of women’s clubs that would help you order a statue for your own town out of a catalog, and they commissioned European sculptors who cashed the checks but privately grumbled about the poor taste of the tacky kitsch they were installing all over America.

We’re still dealing with what they did today. It’s what Charlottesville was about. But most people don’t realize these statues weren’t put there anywhere near the time of the war, or that they were the product of an orchestrated public relations machine. By powerful women!

What was one of the most surprising things you learned from your research?

In almost no instance was a plaque, statue, or sign placed right after the historic event in question. Most of the monuments were actually installed many decades after the event. In the case of the Civil War, most of the memorials were erected in a boom that came a half-century after the last bullet was fired.

If you really get close to the plaques and read past the poetic inscriptions, it quickly becomes clear that our most beloved historic sites aren’t sanctified with artifacts but with propaganda placed there by people who weren’t even witnesses to the event. There was a vast network of women’s clubs that would help you order a statue for your own town out of a catalog, and they commissioned European sculptors who cashed the checks but privately grumbled about the poor taste of the tacky kitsch they were installing all over America.

We’re still dealing with what they did today. It’s what Charlottesville was about. But most people don’t realize these statues weren’t put there anywhere near the time of the war, or that they were the product of an orchestrated public relations machine. By powerful women!

I wrote a line in the book: “Having a Southern heritage is like having herpes—you can forget you have it, you can deny it, but it inevitably bubbles up and requires attention.” These issues aren’t going away.

Places we think of as holy ground, like Arlington National Cemetery, often have some pretty shocking origin stories. Arlington started because some guy got pissed off at Robert E. Lee and started buying corpses in his rose garden to get back at him! That’s our hallowed national burial ground: a nasty practical joke, like the Burn Book from Mean Girls. Dig a little and you find more revolting secrets, like how the incredible number of people buried under the wrong headstone, or the time the government put the remains of a Vietnam soldier in the Tomb of the Unknowns. They pretty much knew his identity, but Ronald Reagan really wanted a TV photo op. So they sealed all the soldier’s belongings in the coffin with him so that no one would figure it out.

They eventually had to admit they’d lied and gave the soldier’s body back to his mom. But if a thing like that happens in a place like Arlington, can the rest of our supposedly sacred sites be taken at face value at all?

It goes a lot deeper. At Ford’s Theatre and the surrender house at Appomattox, the site we visit isn’t even real. They’re fakes! The original buildings are long gone but visitors are rarely told that. The tale’s moral is what’s valued, not the authenticity.

What can visiting these sites teach us about how we remember our past?

Once you realize that all historic sites have been cultivated by someone who wanted to define your understanding of it, you learn how to use critical thinking as a traveler. All it takes is asking questions. One of the most fun threads in the book kicks off when I go to Oakland, a historic but touristy cemetery in Atlanta. I spot an ignored gravestone that piqued my interest. I’d never heard of the name of the woman: Orelia Key Bell. The info desk didn’t have her listed among the notable graves. She was born around the 1860s, which was a very eventful time in Atlanta.

So I took out my phone and right there on her grave, I Googled her. I researched her whole life so I could appreciate what I was seeing. It turned out she was a major poet of her time. I stood there reading PDFs of her books at her feet. Granted, her stuff was dreary, painfully old-fashioned. I wrote that her style of writing didn’t fall out of fashion so much as it was yanked down and clubbed by Hemingway.

But reading her writing at her grave made me feel wildly connected to the past. We almost never go to old places and look deeper. We usually let things remain dead. We accept what’s on the sign or the plaque as gospel, and I’m telling you, almost nothing ever reaches us in a state of purity.

I wrote a line in the book: “Having a Southern heritage is like having herpes—you can forget you have it, you can deny it, but it inevitably bubbles up and requires attention.” These issues aren’t going away.

Places we think of as holy ground, like Arlington National Cemetery, often have some pretty shocking origin stories. Arlington started because some guy got pissed off at Robert E. Lee and started buying corpses in his rose garden to get back at him! That’s our hallowed national burial ground: a nasty practical joke, like the Burn Book from Mean Girls. Dig a little and you find more revolting secrets, like how the incredible number of people buried under the wrong headstone, or the time the government put the remains of a Vietnam soldier in the Tomb of the Unknowns. They pretty much knew his identity, but Ronald Reagan really wanted a TV photo op. So they sealed all the soldier’s belongings in the coffin with him so that no one would figure it out.

They eventually had to admit they’d lied and gave the soldier’s body back to his mom. But if a thing like that happens in a place like Arlington, can the rest of our supposedly sacred sites be taken at face value at all?

It goes a lot deeper. At Ford’s Theatre and the surrender house at Appomattox, the site we visit isn’t even real. They’re fakes! The original buildings are long gone but visitors are rarely told that. The tale’s moral is what’s valued, not the authenticity.

What can visiting these sites teach us about how we remember our past?

Once you realize that all historic sites have been cultivated by someone who wanted to define your understanding of it, you learn how to use critical thinking as a traveler. All it takes is asking questions. One of the most fun threads in the book kicks off when I go to Oakland, a historic but touristy cemetery in Atlanta. I spot an ignored gravestone that piqued my interest. I’d never heard of the name of the woman: Orelia Key Bell. The info desk didn’t have her listed among the notable graves. She was born around the 1860s, which was a very eventful time in Atlanta.

So I took out my phone and right there on her grave, I Googled her. I researched her whole life so I could appreciate what I was seeing. It turned out she was a major poet of her time. I stood there reading PDFs of her books at her feet. Granted, her stuff was dreary, painfully old-fashioned. I wrote that her style of writing didn’t fall out of fashion so much as it was yanked down and clubbed by Hemingway.

But reading her writing at her grave made me feel wildly connected to the past. We almost never go to old places and look deeper. We usually let things remain dead. We accept what’s on the sign or the plaque as gospel, and I’m telling you, almost nothing ever reaches us in a state of purity.

I figured that if I was going to probe all these strangers, I had to be fair and probe someone I knew. I decided to look into an untimely death in my own family, a great-grandfather who had died in a train wreck in 1909. That was the beginning and the end of the tale in my family: “Your great-great grandfather died in a train wreck up in Toccoa.”

But almost as soon as I started looking deeper, I discovered something truly shocking—he had been murdered. Two young Black men were accused in rural South Carolina for sabotaging his train and killing him. You’d think at least someone in my family would have known this! But no one had ever looked into it before!

Here Lies America follows their trail. Who were these guys? Why would they want to kill him? I went to where their village used to be, I started digging into court documents from their murder trial. Let me tell you, the shockers came flooding. Like, I found they may have killed him because they wanted to protect a sacred old Cherokee burial mound from destruction. There was this crazy, larger-than-life forgotten story happening in my own damn family.

My experience with that poet’s grave has a happy coda. Last week, someone told me that Orelia Key Bell and her companion are now officially part of the guided tour of Oakland. The simple act of looking deeper had revived a forgotten life and put her back on the record. That’s what visiting these sites can do—but you have to look behind the veneer, the way I do with dozens of attractions in my book. This is the essence of travel, isn’t it? Getting to a core understanding of the truth of a place.

A lot of what you wrote showed how whitewashed many of these historical sites are. How do we as travelers dig deeper to get to the real history?

Remember that pretty much everything you see at a historic site or museum was intentionally placed there or left there by someone. Ask yourself why. Ask who. And definitely ask when, because the climate of later years often twists interpretation of the past. It’s basic content analysis, really, which is something we’re really bad at in a consumer society.

Americans have it drilled into them to never question the tropes of our patriotism. If we learned about in grade school, we assume it’s a settled matter, and if you press it, you’re somehow an insurgent. Now, more than any other time in history, it’s easier than ever to call up primary sources about any era you want. If you want to go back to what our society really is, if you want to try to figure out how we wandered into the shattered shambles we’re in today, you have to be honest about the forces that created the image that, until recently, many of us believed we really were.

I figured that if I was going to probe all these strangers, I had to be fair and probe someone I knew. I decided to look into an untimely death in my own family, a great-grandfather who had died in a train wreck in 1909. That was the beginning and the end of the tale in my family: “Your great-great grandfather died in a train wreck up in Toccoa.”

But almost as soon as I started looking deeper, I discovered something truly shocking—he had been murdered. Two young Black men were accused in rural South Carolina for sabotaging his train and killing him. You’d think at least someone in my family would have known this! But no one had ever looked into it before!

Here Lies America follows their trail. Who were these guys? Why would they want to kill him? I went to where their village used to be, I started digging into court documents from their murder trial. Let me tell you, the shockers came flooding. Like, I found they may have killed him because they wanted to protect a sacred old Cherokee burial mound from destruction. There was this crazy, larger-than-life forgotten story happening in my own damn family.

My experience with that poet’s grave has a happy coda. Last week, someone told me that Orelia Key Bell and her companion are now officially part of the guided tour of Oakland. The simple act of looking deeper had revived a forgotten life and put her back on the record. That’s what visiting these sites can do—but you have to look behind the veneer, the way I do with dozens of attractions in my book. This is the essence of travel, isn’t it? Getting to a core understanding of the truth of a place.

A lot of what you wrote showed how whitewashed many of these historical sites are. How do we as travelers dig deeper to get to the real history?

Remember that pretty much everything you see at a historic site or museum was intentionally placed there or left there by someone. Ask yourself why. Ask who. And definitely ask when, because the climate of later years often twists interpretation of the past. It’s basic content analysis, really, which is something we’re really bad at in a consumer society.

Americans have it drilled into them to never question the tropes of our patriotism. If we learned about in grade school, we assume it’s a settled matter, and if you press it, you’re somehow an insurgent. Now, more than any other time in history, it’s easier than ever to call up primary sources about any era you want. If you want to go back to what our society really is, if you want to try to figure out how we wandered into the shattered shambles we’re in today, you have to be honest about the forces that created the image that, until recently, many of us believed we really were.

Do you think Americans have a problem talking about their history? If so, why is that?

There’s a phrase, and I forget who said it—maybe James Baldwin?-but it goes, “Americans are better at thinking with their feelings than about them.” We go by feels, not so much by facts. We do love to cling to a tidy mythology of how free and wonderful our country always was. It reassures us. We probably need it. After all, in America, where we all come from different places, our national self-belief is our main cultural glue. So we can’t resist prettying up the horrible things we do.

But make no mistake: Violence was the foundation of power in the 1800s, and violence is still a foundation of our values and entertainment today. We have yet to come to terms with that. Our way of dealing with violence is usually to convince ourselves it’s noble.

And if we can’t make pain noble, we try to erase it. It’s why the place where McKinley was shot, in Buffalo, lies under a road now. That was intentional so that it would be forgotten by anarchists. McKinley was given no significant pilgrimage spot where he died, but right after that death, his fans paid for a monument by Burnside’s Bridge in Antietam, because as a youth, he once served coffee to soldiers.

That’s the reason: “personally and without orders served hot coffee,” it reads—it’s hilarious. That is our national mythmaking in a nutshell: Don’t pay attention to the place that raises tough questions about imperialism and economic disparity, but put up an expensive tribute to a barista.

What is the main takeaway you’d like readers to take away from your book?

You may not know where you came from as well as you think you do. And we as a society definitely haven’t asked enough questions about who shaped the information we grew up with. Americans are finally ready to hear some truth.

Jason Cochran is the author of Here Lies America: Buried Agendas and Family Secrets at the Tourist Sites Where Bad History Went Down. He’s been a writer since mid-1990s, a commentator on CBS and AOL, and works today as editor-in-chief of Frommers.com and as co-host of the Frommer Travel Show on WABC. Jason was twice awarded “Guide Book of the Year” by the Lowell Thomas Awards and the North American Travel Journalists Association.

Do you think Americans have a problem talking about their history? If so, why is that?

There’s a phrase, and I forget who said it—maybe James Baldwin?-but it goes, “Americans are better at thinking with their feelings than about them.” We go by feels, not so much by facts. We do love to cling to a tidy mythology of how free and wonderful our country always was. It reassures us. We probably need it. After all, in America, where we all come from different places, our national self-belief is our main cultural glue. So we can’t resist prettying up the horrible things we do.

But make no mistake: Violence was the foundation of power in the 1800s, and violence is still a foundation of our values and entertainment today. We have yet to come to terms with that. Our way of dealing with violence is usually to convince ourselves it’s noble.

And if we can’t make pain noble, we try to erase it. It’s why the place where McKinley was shot, in Buffalo, lies under a road now. That was intentional so that it would be forgotten by anarchists. McKinley was given no significant pilgrimage spot where he died, but right after that death, his fans paid for a monument by Burnside’s Bridge in Antietam, because as a youth, he once served coffee to soldiers.

That’s the reason: “personally and without orders served hot coffee,” it reads—it’s hilarious. That is our national mythmaking in a nutshell: Don’t pay attention to the place that raises tough questions about imperialism and economic disparity, but put up an expensive tribute to a barista.

What is the main takeaway you’d like readers to take away from your book?

You may not know where you came from as well as you think you do. And we as a society definitely haven’t asked enough questions about who shaped the information we grew up with. Americans are finally ready to hear some truth.

Jason Cochran is the author of Here Lies America: Buried Agendas and Family Secrets at the Tourist Sites Where Bad History Went Down. He’s been a writer since mid-1990s, a commentator on CBS and AOL, and works today as editor-in-chief of Frommers.com and as co-host of the Frommer Travel Show on WABC. Jason was twice awarded “Guide Book of the Year” by the Lowell Thomas Awards and the North American Travel Journalists Association.